I Survived the Death Ride

"This is the inky-black heart of the ride."

It was probably about 11 a.m., on the day of the 30th annual Death Ride. I'd been in the saddle six hours, working my way to the top of the third of five climbs of the day, this one to Ebbetts Pass. I had ridden up behind a rider and we engaged in a friendly conversation for a few minutes. As the road began to steepen, my new companion warmed me that we were at the crux of the entire day's ride.

(Note: click on images for larger versions.)

(Note: click on images for larger versions.) The trip had begun the day before. Heading north, I met my friend Richard Nolthenius in Santa Nella, California, off Interstate-5, in the Central Valley of California. Leaving my vehicle in the parking lot at the Pea Soup Andersen Motel, I transferred my bike and my gear to Richard's car. We were off, for the 3 hour and 45 minutes drive across the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the little town of Markleeville, southeast of Lake Tahoe.

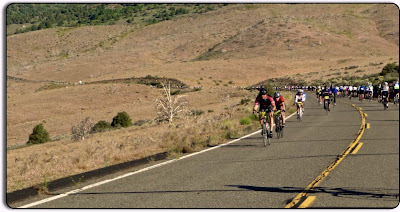

Markleeville was hosting the Death Ride, which boasts 129 miles and 15,000 feet of climbing in one day, through some of the more spectacular realms on the east side of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, in well-named Alpine County.

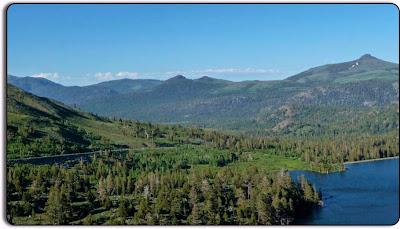

The Sierras are the geographical spine of California, a granitic leviathan that is the longest unbroken mountain chain in the U.S. We drove up through the dry foothills, into historic Gold Rush country, over Highway scenic 4, which narrowed and began to twist and turn through some spectacular terrain, lifting us through a thick forest of ponderosa and lodgepole pines. The highway is, I think, one of the most scenic back roads in California, and I should know, as I wrote the book.

The Sierras are the geographical spine of California, a granitic leviathan that is the longest unbroken mountain chain in the U.S. We drove up through the dry foothills, into historic Gold Rush country, over Highway scenic 4, which narrowed and began to twist and turn through some spectacular terrain, lifting us through a thick forest of ponderosa and lodgepole pines. The highway is, I think, one of the most scenic back roads in California, and I should know, as I wrote the book.

We reached Markleeville – that's it above, and that's about all of the town – and headed to nearby Turtle Park, where I registered for the ride. We found a lovely campsite less than a mile from the park, on national forest land; our spot overlooked a little lake. Nearby two other riders had set up their own camp. Richard made the perfect dinner: lots of pasta with chicken.

We reached Markleeville – that's it above, and that's about all of the town – and headed to nearby Turtle Park, where I registered for the ride. We found a lovely campsite less than a mile from the park, on national forest land; our spot overlooked a little lake. Nearby two other riders had set up their own camp. Richard made the perfect dinner: lots of pasta with chicken.

Sunset orchestrated a grand show; in the distance, as night came on, black clouds that had built throughout the late afternoon were illuminated from within by lightning. The show was far enough away that we heard no thunder.

Sunset orchestrated a grand show; in the distance, as night came on, black clouds that had built throughout the late afternoon were illuminated from within by lightning. The show was far enough away that we heard no thunder.

After a fitful night of sleep, which left me with plenty of time to ponder what I was doing, and why, we woke at 4:00 a.m., with the impressive Milky Way overhead, a sight not visible from my home in Los Angeles. By 5 a.m. we were at the entrance to Turtle Park, ready to officially begin the Death Ride.

After a fitful night of sleep, which left me with plenty of time to ponder what I was doing, and why, we woke at 4:00 a.m., with the impressive Milky Way overhead, a sight not visible from my home in Los Angeles. By 5 a.m. we were at the entrance to Turtle Park, ready to officially begin the Death Ride.

Richard decided to take his time; he only wanted to climb two passes. I quickly glided away from him on the downhill that begins the ride. Events like this one are friendly affairs, and as dawn illuminated the scene, I met Denali Schmidt. He mentioned that he'd just finished attending Cabrillo College, in Santa Cruz, California.

Richard decided to take his time; he only wanted to climb two passes. I quickly glided away from him on the downhill that begins the ride. Events like this one are friendly affairs, and as dawn illuminated the scene, I met Denali Schmidt. He mentioned that he'd just finished attending Cabrillo College, in Santa Cruz, California.

After two hours of steady riding, I reached the top of Monitor Pass, at 8,314 feet above sea level; I'd pedaled about 15 miles, with 2,800 feet of gain. The altitude didn't seem to bother me, I think because of my pace. The first rest stop, just below the pass, is in the photo below. A volunteer affixed a purple sticker to my bib number, signifying that I'd completed the first pass. One down, four stickers to go.

After two hours of steady riding, I reached the top of Monitor Pass, at 8,314 feet above sea level; I'd pedaled about 15 miles, with 2,800 feet of gain. The altitude didn't seem to bother me, I think because of my pace. The first rest stop, just below the pass, is in the photo below. A volunteer affixed a purple sticker to my bib number, signifying that I'd completed the first pass. One down, four stickers to go.

Meanwhile, the seemingly unending river of cyclists was flowing uphill all around me. Many if not most riders seemed to have triple cranksets on their bikes. Most of the time, on the uphills, riders seemed to be in their lowest gears. Most of the time I was in my lowest gears, too. I had a 26 tooth inner chainring on my triple crankset, and a 27 tooth cog on my rear cassette; that combination was more than low enough when I needed it, and I was glad I decided not to switch to even lower gears, which I'd contemplated for a few days; I'd have worn myself out with useless spinning.

Meanwhile, the seemingly unending river of cyclists was flowing uphill all around me. Many if not most riders seemed to have triple cranksets on their bikes. Most of the time, on the uphills, riders seemed to be in their lowest gears. Most of the time I was in my lowest gears, too. I had a 26 tooth inner chainring on my triple crankset, and a 27 tooth cog on my rear cassette; that combination was more than low enough when I needed it, and I was glad I decided not to switch to even lower gears, which I'd contemplated for a few days; I'd have worn myself out with useless spinning.

Returning to Monitor Pass, I had a great view of a massive peak, still showing some snow in mid-July.

Returning to Monitor Pass, I had a great view of a massive peak, still showing some snow in mid-July.

After another thrilling descent down the way I'd come up early in the morning, I met up with a Death Ride veteran. It was he who called this the ink-black heart of the ride. I'm not sure it that was true for me; I know it was the pass on which I suffered a significant, but short-lived cramp, in my right leg, just below the summit.

After another thrilling descent down the way I'd come up early in the morning, I met up with a Death Ride veteran. It was he who called this the ink-black heart of the ride. I'm not sure it that was true for me; I know it was the pass on which I suffered a significant, but short-lived cramp, in my right leg, just below the summit.

Rather than stop at the well-stocked rest station at the summit, and rather than turn around and wisely conclude my day of riding, I opted to drop down to the far side of Ebbetts on another lengthy descent. I spent several minutes downing a few cans of V8 juice, and munching handfuls of potato chips, at the rest stop; I also ate several crackers topped with peanut butter and a slice of banana. For the first time, I took a serious break from riding and relaxed in the shade for a few minutes.

Rather than stop at the well-stocked rest station at the summit, and rather than turn around and wisely conclude my day of riding, I opted to drop down to the far side of Ebbetts on another lengthy descent. I spent several minutes downing a few cans of V8 juice, and munching handfuls of potato chips, at the rest stop; I also ate several crackers topped with peanut butter and a slice of banana. For the first time, I took a serious break from riding and relaxed in the shade for a few minutes.

At the lunch stop, having eaten a fair amount at other rest stops, I opted for more potato chips and skipped the official meal.

At the lunch stop, having eaten a fair amount at other rest stops, I opted for more potato chips and skipped the official meal.

Meeting up with Richard in "downtown" Markleeville, I decided to push for the top of the final pass, 24 miles and some few thousand feet above me. It was 2 p.m. About an hour later, I reached the community of Woodfords, where I relaxed for several minutes.

Meeting up with Richard in "downtown" Markleeville, I decided to push for the top of the final pass, 24 miles and some few thousand feet above me. It was 2 p.m. About an hour later, I reached the community of Woodfords, where I relaxed for several minutes.

After more potato chips, a Clif Bar, watermelon and one of the several Coke's I drank during the day, I spent a few pleasant moments with a new friend. That's me, on the right, in my 2001 finisher's jersey of the Climb to Kaiser, a ride similar to the Death Ride that takes place each year on the west side of the Sierras.

After more potato chips, a Clif Bar, watermelon and one of the several Coke's I drank during the day, I spent a few pleasant moments with a new friend. That's me, on the right, in my 2001 finisher's jersey of the Climb to Kaiser, a ride similar to the Death Ride that takes place each year on the west side of the Sierras.

With the temperature apparently about 90 degrees, the shower was a popular form of baptism for the rigors of the road ahead, which took us up a steep canyon for another half dozen miles or so in skies devoid of the expected thunderclouds.

With the temperature apparently about 90 degrees, the shower was a popular form of baptism for the rigors of the road ahead, which took us up a steep canyon for another half dozen miles or so in skies devoid of the expected thunderclouds.

Once in a while I'd pick up a little speed to join a rider or a group of riders in front of me. All of these riders would at some point speed up, and I managed, at my steady pace, to catch almost all of them again. Meanwhile, riders were passing me, pacing me, and falling off my lead as we all relentlessly ground out the miles.

Once in a while I'd pick up a little speed to join a rider or a group of riders in front of me. All of these riders would at some point speed up, and I managed, at my steady pace, to catch almost all of them again. Meanwhile, riders were passing me, pacing me, and falling off my lead as we all relentlessly ground out the miles.

Once we rose above the valley, what a challenging set of final miles there were. Time and space seemed to stretch out before me. Sometimes I was in my lowest gear and sometimes my rear end wanted off the saddle. (In a stroke of strategic genius, I'd replaced my expensive, minimalist racing saddle, which had caused me some unusual trouble on training rides the past few weeks. In its place, I opted for an "old school," hand-made, leather Brooks saddle. I was quite comfortable most of the time, although, compared to my regular saddle, the Brooks weighed about a pound more).

Once we rose above the valley, what a challenging set of final miles there were. Time and space seemed to stretch out before me. Sometimes I was in my lowest gear and sometimes my rear end wanted off the saddle. (In a stroke of strategic genius, I'd replaced my expensive, minimalist racing saddle, which had caused me some unusual trouble on training rides the past few weeks. In its place, I opted for an "old school," hand-made, leather Brooks saddle. I was quite comfortable most of the time, although, compared to my regular saddle, the Brooks weighed about a pound more).

I had my celebratory ice cream (two, actually), accepted congratulations from one of the 700 support staff who were so helpful during the day, and received my finisher's pin and final bib sticker, proof that I'd completed all five passes of the 2010 Death Ride.

I had my celebratory ice cream (two, actually), accepted congratulations from one of the 700 support staff who were so helpful during the day, and received my finisher's pin and final bib sticker, proof that I'd completed all five passes of the 2010 Death Ride.

As did the others who had completed pedaling up five-passes, I participated in the traditional signing of the finishers' board. Why others would make such an arduous ride I do know know; for me, though signing the board was tangible proof that I still have what it takes, that I'm still vital, that I'm alive.

As did the others who had completed pedaling up five-passes, I participated in the traditional signing of the finishers' board. Why others would make such an arduous ride I do know know; for me, though signing the board was tangible proof that I still have what it takes, that I'm still vital, that I'm alive.

And then began the 20-mile return to Turtle Rock Park, where Richard graciously waited for me. Some hours later, recrossing the Sierra Nevada and retracing our way to Santa Nella, I took a room at the motel. After a shower, I replayed the day in my mind as I drifted into a deep, inky-black sleep, knowing with satisfaction that I was both a survivor and victor of the Death Ride.

And then began the 20-mile return to Turtle Rock Park, where Richard graciously waited for me. Some hours later, recrossing the Sierra Nevada and retracing our way to Santa Nella, I took a room at the motel. After a shower, I replayed the day in my mind as I drifted into a deep, inky-black sleep, knowing with satisfaction that I was both a survivor and victor of the Death Ride.

The Sierras are the geographical spine of California, a granitic leviathan that is the longest unbroken mountain chain in the U.S. We drove up through the dry foothills, into historic Gold Rush country, over Highway scenic 4, which narrowed and began to twist and turn through some spectacular terrain, lifting us through a thick forest of ponderosa and lodgepole pines. The highway is, I think, one of the most scenic back roads in California, and I should know, as I wrote the book.

The Sierras are the geographical spine of California, a granitic leviathan that is the longest unbroken mountain chain in the U.S. We drove up through the dry foothills, into historic Gold Rush country, over Highway scenic 4, which narrowed and began to twist and turn through some spectacular terrain, lifting us through a thick forest of ponderosa and lodgepole pines. The highway is, I think, one of the most scenic back roads in California, and I should know, as I wrote the book. We reached Markleeville – that's it above, and that's about all of the town – and headed to nearby Turtle Park, where I registered for the ride. We found a lovely campsite less than a mile from the park, on national forest land; our spot overlooked a little lake. Nearby two other riders had set up their own camp. Richard made the perfect dinner: lots of pasta with chicken.

We reached Markleeville – that's it above, and that's about all of the town – and headed to nearby Turtle Park, where I registered for the ride. We found a lovely campsite less than a mile from the park, on national forest land; our spot overlooked a little lake. Nearby two other riders had set up their own camp. Richard made the perfect dinner: lots of pasta with chicken. Sunset orchestrated a grand show; in the distance, as night came on, black clouds that had built throughout the late afternoon were illuminated from within by lightning. The show was far enough away that we heard no thunder.

Sunset orchestrated a grand show; in the distance, as night came on, black clouds that had built throughout the late afternoon were illuminated from within by lightning. The show was far enough away that we heard no thunder. Richard and I were both looking forward to the predicted afternoon clouds to help keep us cool, and other cyclists we met told us that was the usual summer weather pattern, particularly over Carson Pass.

Later, under a bright canopy of stars, we watched the International Space Station glide silently through the sky, a point of light reflecting the light of the sun which was now far, far below the horizon.

After a fitful night of sleep, which left me with plenty of time to ponder what I was doing, and why, we woke at 4:00 a.m., with the impressive Milky Way overhead, a sight not visible from my home in Los Angeles. By 5 a.m. we were at the entrance to Turtle Park, ready to officially begin the Death Ride.

After a fitful night of sleep, which left me with plenty of time to ponder what I was doing, and why, we woke at 4:00 a.m., with the impressive Milky Way overhead, a sight not visible from my home in Los Angeles. By 5 a.m. we were at the entrance to Turtle Park, ready to officially begin the Death Ride. Richard decided to take his time; he only wanted to climb two passes. I quickly glided away from him on the downhill that begins the ride. Events like this one are friendly affairs, and as dawn illuminated the scene, I met Denali Schmidt. He mentioned that he'd just finished attending Cabrillo College, in Santa Cruz, California.

Richard decided to take his time; he only wanted to climb two passes. I quickly glided away from him on the downhill that begins the ride. Events like this one are friendly affairs, and as dawn illuminated the scene, I met Denali Schmidt. He mentioned that he'd just finished attending Cabrillo College, in Santa Cruz, California."Do you happen to know the astronomy instructor?"

"Richard Nolthenius?" Denali answered.

"He's a little behind us," I answered.

"I love him; he's the best teacher!"

It's a small world.

After we reached the Highway 4-Highway 89 junction, which was our turnoff to Monitor Pass, Denali pulled away from me. The sun crept above the horizon to light up the tops of the peaks to the west.

After we reached the Highway 4-Highway 89 junction, which was our turnoff to Monitor Pass, Denali pulled away from me. The sun crept above the horizon to light up the tops of the peaks to the west.

After we reached the Highway 4-Highway 89 junction, which was our turnoff to Monitor Pass, Denali pulled away from me. The sun crept above the horizon to light up the tops of the peaks to the west.

After we reached the Highway 4-Highway 89 junction, which was our turnoff to Monitor Pass, Denali pulled away from me. The sun crept above the horizon to light up the tops of the peaks to the west. Many, many riders passed me, and I passed a few in return; I had several more usually brief conversations. As usual, it took me a good hour to warm up to my task. For the most park, I stuck to a slow and steady pace, the better to let me enjoy the views of the mountains and the splashy patches of colorful wildflowers, including blue lupine and yellow sky pilots; I also knew I had to conserve my energy for the climbs ahead, as many of them as I could notch. "Don't think about what's ahead, just pedal one stroke at a time," my friend, Jean Ray, had suggested. It was good advice.

After two hours of steady riding, I reached the top of Monitor Pass, at 8,314 feet above sea level; I'd pedaled about 15 miles, with 2,800 feet of gain. The altitude didn't seem to bother me, I think because of my pace. The first rest stop, just below the pass, is in the photo below. A volunteer affixed a purple sticker to my bib number, signifying that I'd completed the first pass. One down, four stickers to go.

After two hours of steady riding, I reached the top of Monitor Pass, at 8,314 feet above sea level; I'd pedaled about 15 miles, with 2,800 feet of gain. The altitude didn't seem to bother me, I think because of my pace. The first rest stop, just below the pass, is in the photo below. A volunteer affixed a purple sticker to my bib number, signifying that I'd completed the first pass. One down, four stickers to go.At the feeding station, a boy of about 12 called out, 'We've got Clif Bars, potato chips, potatoes, watermelon, cookies, oranges, nuts, bagels, water and Cytomax!"

Not lingering, I ate some food (I was happiest with the chips, because a year before, on my Buffalo Pass ride, I'd bonked, and learned the value, for me, of replacing salt. I also paid a visit to one of the many portable toilets, a good sign that I was staying hydrated.

I enjoyed what was a mind-blowing, ten-mile descent from Monitor Pass down toward Highway 395. I doubt I've ever had as much fun descending from on high. At the bottom, I took a few minutes to resupply on food, water, and a sports drink, and then I turned around and headed the tough ten miles back up the pass, the way I'd just come.

On the way down, I'd passed hundreds of riders coming up. Just how early had these people started the ride? Would I have time, even if I were capable, of finishing the five passes?

Now, as I joined the long line climbing back to Monitor Pass, I watched riders shoot down the pavement. Not only did I watch them, I could hear them, as their bikes buzzed over the pavement. I thought I could almost hear the bikes split the air, too. Some riders were able to reach speeds well over 50 mph.

Many minutes later, I looked back the way I had come. Click on the photo below and it's possible to see a thin, gray line that is the roadway, far below.

Here is the same scene, below, made with the telephoto setting on my little camera. It was heartening, in a way, to see so many others struggling up the mountain from the desert, little ants of the undead pedaling away.

Meanwhile, the seemingly unending river of cyclists was flowing uphill all around me. Many if not most riders seemed to have triple cranksets on their bikes. Most of the time, on the uphills, riders seemed to be in their lowest gears. Most of the time I was in my lowest gears, too. I had a 26 tooth inner chainring on my triple crankset, and a 27 tooth cog on my rear cassette; that combination was more than low enough when I needed it, and I was glad I decided not to switch to even lower gears, which I'd contemplated for a few days; I'd have worn myself out with useless spinning.

Meanwhile, the seemingly unending river of cyclists was flowing uphill all around me. Many if not most riders seemed to have triple cranksets on their bikes. Most of the time, on the uphills, riders seemed to be in their lowest gears. Most of the time I was in my lowest gears, too. I had a 26 tooth inner chainring on my triple crankset, and a 27 tooth cog on my rear cassette; that combination was more than low enough when I needed it, and I was glad I decided not to switch to even lower gears, which I'd contemplated for a few days; I'd have worn myself out with useless spinning.

Returning to Monitor Pass, I had a great view of a massive peak, still showing some snow in mid-July.

Returning to Monitor Pass, I had a great view of a massive peak, still showing some snow in mid-July. After another thrilling descent down the way I'd come up early in the morning, I met up with a Death Ride veteran. It was he who called this the ink-black heart of the ride. I'm not sure it that was true for me; I know it was the pass on which I suffered a significant, but short-lived cramp, in my right leg, just below the summit.

After another thrilling descent down the way I'd come up early in the morning, I met up with a Death Ride veteran. It was he who called this the ink-black heart of the ride. I'm not sure it that was true for me; I know it was the pass on which I suffered a significant, but short-lived cramp, in my right leg, just below the summit. On the way up, there certainly were many steep grades and some extremely sharp hairpin turns, and near-hallucinogenic views out over the canyon we were ascending. There was a view of a beautiful waterfall and a little lake to savor before finally topping out. There had been a few water stops, too, for those cyclists who were running dry. To forestall more cramps, I downed a couple of electrolyte tablets, which I'd been swallowing at the top and bottom of the climbs.

Rather than stop at the well-stocked rest station at the summit, and rather than turn around and wisely conclude my day of riding, I opted to drop down to the far side of Ebbetts on another lengthy descent. I spent several minutes downing a few cans of V8 juice, and munching handfuls of potato chips, at the rest stop; I also ate several crackers topped with peanut butter and a slice of banana. For the first time, I took a serious break from riding and relaxed in the shade for a few minutes.

Rather than stop at the well-stocked rest station at the summit, and rather than turn around and wisely conclude my day of riding, I opted to drop down to the far side of Ebbetts on another lengthy descent. I spent several minutes downing a few cans of V8 juice, and munching handfuls of potato chips, at the rest stop; I also ate several crackers topped with peanut butter and a slice of banana. For the first time, I took a serious break from riding and relaxed in the shade for a few minutes. Worried about cramps, I gingerly began my ride back up Ebbetts; as I progressed, I felt stronger, although the climb seemed unending and I have only a hazy blur of a memory of making the top of the pass, at 8,730 feet above sea level. I do remember someone from the support crew held out Red Vine sticks, and I happily grabbed one. Once again, though, I decided to skip the Ebbetts Pass rest stop. While my water bottles were less than full, I knew more water was waiting for me at the bottom of the grade.

On the downside, after a wickedly-twisting descent that was as beautiful and exciting as the run down Monitor had been a few hours earlier, I stopped to photograph some of the "Wild Women of Ebbetts Pass." Who they were, why there were, must for now remain a mystery, but they were happy to pose for a photograph and encourage me to continue the ride.

At the lunch stop, having eaten a fair amount at other rest stops, I opted for more potato chips and skipped the official meal.

At the lunch stop, having eaten a fair amount at other rest stops, I opted for more potato chips and skipped the official meal. Meeting up with Richard in "downtown" Markleeville, I decided to push for the top of the final pass, 24 miles and some few thousand feet above me. It was 2 p.m. About an hour later, I reached the community of Woodfords, where I relaxed for several minutes.

Meeting up with Richard in "downtown" Markleeville, I decided to push for the top of the final pass, 24 miles and some few thousand feet above me. It was 2 p.m. About an hour later, I reached the community of Woodfords, where I relaxed for several minutes. After more potato chips, a Clif Bar, watermelon and one of the several Coke's I drank during the day, I spent a few pleasant moments with a new friend. That's me, on the right, in my 2001 finisher's jersey of the Climb to Kaiser, a ride similar to the Death Ride that takes place each year on the west side of the Sierras.

After more potato chips, a Clif Bar, watermelon and one of the several Coke's I drank during the day, I spent a few pleasant moments with a new friend. That's me, on the right, in my 2001 finisher's jersey of the Climb to Kaiser, a ride similar to the Death Ride that takes place each year on the west side of the Sierras. With the temperature apparently about 90 degrees, the shower was a popular form of baptism for the rigors of the road ahead, which took us up a steep canyon for another half dozen miles or so in skies devoid of the expected thunderclouds.

With the temperature apparently about 90 degrees, the shower was a popular form of baptism for the rigors of the road ahead, which took us up a steep canyon for another half dozen miles or so in skies devoid of the expected thunderclouds.  Once in a while I'd pick up a little speed to join a rider or a group of riders in front of me. All of these riders would at some point speed up, and I managed, at my steady pace, to catch almost all of them again. Meanwhile, riders were passing me, pacing me, and falling off my lead as we all relentlessly ground out the miles.

Once in a while I'd pick up a little speed to join a rider or a group of riders in front of me. All of these riders would at some point speed up, and I managed, at my steady pace, to catch almost all of them again. Meanwhile, riders were passing me, pacing me, and falling off my lead as we all relentlessly ground out the miles.At the final rest stop, where the road had mercifully flattened out, I rested in the shade, sitting with my back against the side of a car. As I sat, my right leg suddenly cramped again, and for a while I felt dizzy and nauseous. Was I feeling my age? No, it was just the reaction of a body I hadn't trained hard enough.

Once I threw my leg over my bike's top bar and began pedaling, I felt well enough again. There were only nine miles left to reach Carson Pass, as we pedaled through the bosom of Hope Valley.

Once we rose above the valley, what a challenging set of final miles there were. Time and space seemed to stretch out before me. Sometimes I was in my lowest gear and sometimes my rear end wanted off the saddle. (In a stroke of strategic genius, I'd replaced my expensive, minimalist racing saddle, which had caused me some unusual trouble on training rides the past few weeks. In its place, I opted for an "old school," hand-made, leather Brooks saddle. I was quite comfortable most of the time, although, compared to my regular saddle, the Brooks weighed about a pound more).

Once we rose above the valley, what a challenging set of final miles there were. Time and space seemed to stretch out before me. Sometimes I was in my lowest gear and sometimes my rear end wanted off the saddle. (In a stroke of strategic genius, I'd replaced my expensive, minimalist racing saddle, which had caused me some unusual trouble on training rides the past few weeks. In its place, I opted for an "old school," hand-made, leather Brooks saddle. I was quite comfortable most of the time, although, compared to my regular saddle, the Brooks weighed about a pound more). The roads, closed to traffic on the other passes, were open now, and there was a parade of vehicles for a while; many cars and trucks had bikes attached to racks belonging to those who had finished the ride earlier.

I had my celebratory ice cream (two, actually), accepted congratulations from one of the 700 support staff who were so helpful during the day, and received my finisher's pin and final bib sticker, proof that I'd completed all five passes of the 2010 Death Ride.

I had my celebratory ice cream (two, actually), accepted congratulations from one of the 700 support staff who were so helpful during the day, and received my finisher's pin and final bib sticker, proof that I'd completed all five passes of the 2010 Death Ride. As did the others who had completed pedaling up five-passes, I participated in the traditional signing of the finishers' board. Why others would make such an arduous ride I do know know; for me, though signing the board was tangible proof that I still have what it takes, that I'm still vital, that I'm alive.

As did the others who had completed pedaling up five-passes, I participated in the traditional signing of the finishers' board. Why others would make such an arduous ride I do know know; for me, though signing the board was tangible proof that I still have what it takes, that I'm still vital, that I'm alive.  And then began the 20-mile return to Turtle Rock Park, where Richard graciously waited for me. Some hours later, recrossing the Sierra Nevada and retracing our way to Santa Nella, I took a room at the motel. After a shower, I replayed the day in my mind as I drifted into a deep, inky-black sleep, knowing with satisfaction that I was both a survivor and victor of the Death Ride.

And then began the 20-mile return to Turtle Rock Park, where Richard graciously waited for me. Some hours later, recrossing the Sierra Nevada and retracing our way to Santa Nella, I took a room at the motel. After a shower, I replayed the day in my mind as I drifted into a deep, inky-black sleep, knowing with satisfaction that I was both a survivor and victor of the Death Ride.Note: click on images for larger versions.

6 comments:

Thanks for the sharp photos and memories! Look forward already to 2011.

Great account of the ride... we work the Ebbetts aid station and don't get to experience the "rest" of the ride... I'm going to post a link to this on our FB page... many thanks!

Warren Alford, Ebbetts Pass

loved it!

Nice review. I think I took a picture of you at Monitor Pass (and you took my photo too). I remember your CTK jersey.

Be Steel - You did make my photo, and I saw the one I took of you (you did a better job than me, as I see I cut off part of the Ebbetts Pass sign).

I road me bike in high school and in college,

mainly for training to race, many years ago, so

Great i'm glad

you made it and

enjoyed yourself.

i continue to look

forward to your bloging.

especially of L.A.;

maybe on the camino real

too? regards.

Post a Comment